Don't Worry About Long Standups

In most places, a standup that lasts more than 10-15 minutes is an anti-pattern. As Jason Yip says on Martin Fowler’s blog (the de facto source of definitions for any controversial tech topic these days):

We stand up to keep the meeting short.

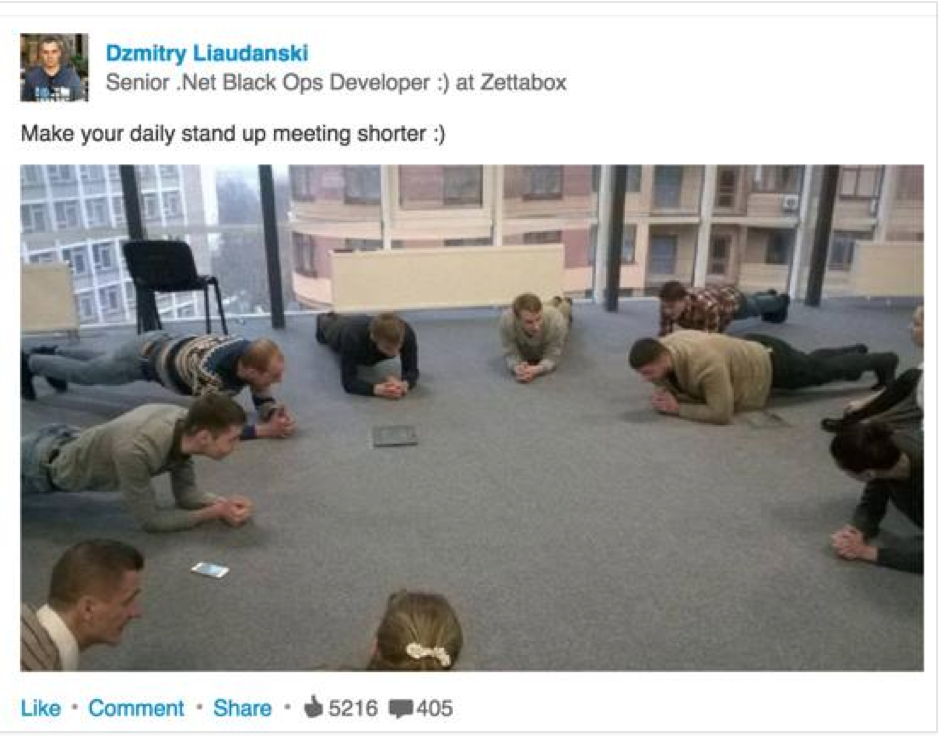

This has become such a nostrum that people have adopted extreme measures to avoid long standups:

However, no rule is without exceptions. First principles always apply.

Recently I joined a team where the daily standup lasts 20-30 minutes (for 7-8 people.) And yet it’s never a problem. Why?

Because it’s a 100% remote team. People across 5 time zones who all work from home. The standup is our one chance in the day to catch up with each other. Working from home is lonely - it’s good to swap stories, tell jokes, just generally connect. We get a lot done, and we have fun.

In fact, we are a lot like Team B in this Google study:

Imagine you have been invited to join one of two groups.

Team A is composed of people who are all exceptionally smart and successful. When you watch a video of this group working, you see professionals who wait until a topic arises in which they are expert, and then they speak at length, explaining what the group ought to do. When someone makes a side comment, the speaker stops, reminds everyone of the agenda and pushes the meeting back on track. This team is efficient. There is no idle chitchat or long debates. The meeting ends as scheduled and disbands so everyone can get back to their desks.

Team B is different. It’s evenly divided between successful executives and middle managers with few professional accomplishments. Teammates jump in and out of discussions. People interject and complete one another’s thoughts. When a team member abruptly changes the topic, the rest of the group follows him off the agenda. At the end of the meeting, the meeting doesn’t actually end: Everyone sits around to gossip and talk about their lives.

[…] if you are given a choice between the serious-minded Team A or the free-flowing Team B, you should probably opt for Team B. Team A may be filled with smart people, all optimized for peak individual efficiency. But the group’s norms discourage equal speaking; there are few exchanges of the kind of personal information that lets teammates pick up on what people are feeling or leaving unsaid. There’s a good chance the members of Team A will continue to act like individuals once they come together, and there’s little to suggest that, as a group, they will become more collectively intelligent.

In contrast, on Team B, people may speak over one another, go on tangents and socialize instead of remaining focused on the agenda. The team may seem inefficient to a casual observer. But all the team members speak as much as they need to. They are sensitive to one another’s moods and share personal stories and emotions. While Team B might not contain as many individual stars, the sum will be greater than its parts.

So the next time you’re tempted to say “this meeting is going too long” - look beyond just the time taken. Evaluate whether there’s value in the conversations being had (work or otherwise) and reeavaluate what bounds need to be put on them.